A decade old research by NIO in

collaboration with French scientists have found out that a river flows in the

Bay of Bengal along the east coast starting from the estuary of Ganges up to

the tip of South India. The waters poured into the Bay of Bengal by Ganges and

Brahmaputra and the east flowing rivers such as Mahanadhi, Godavari and Krishna

flow together for a width of 100 km down towards the south and to a depth of 40

meters from the surface. These rivers pour nearly 1100 cubic kilometres of

fresh water from the monsoon rains into the Bay. Thus by the time the monsoon

season gets over, this fresh water poured into the Bay by these rivers flow along

the east coast and reach the tip of the South India and even circling Srilanka.

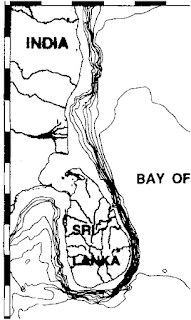

The researchers have come up with this map of the flow of this river in the

Bay.

Arrows

showing the origin of the 'river in sea' in the Bay of Bengal all the way to

the end. Locations from where fishermen collected water samples are named along

the coast.

© Gopalakrishna, V. V. et al.

This discovery is a confirmation of what I have been

repeatedly writing from 2008 onwards - on the presence of a channel bordering the

east coastal line of South India, dug by the sons of King Sagara, the ancestor

of Rama in which the river Ganges flowed down for the first time after the

Gangotri melted to form the Ganges river. My detailed article in Tamil written

in 2011 can be read

here.

The digging ended at Setu in Rameswaram (read

here).

The Sagaras went on digging around Srilanka, circled it and ended up at Setu as

that place (Setu) was hard to dig and had hot springs. The Ramayana description

of Minaka Mountain encountered by Hanuman shows that there was volcanism or a vent

in the mantle cover underneath that place. This is a fact, as studies done by

the Geological Survey of India have found out hot springs of 60 to 70 degree Celsius

along the Setu bund. (Read

here). (The sea near this place in Rameswaram is called as Agni Theertham

even today). The heat of the springs had killed the Sagaras. Their ashes washed

by the River Ganga could give them salvation. It was for this reason Bhagiratha,

the descendant of Sagara, did penance to bring Ganga from the Himalayas.

What had actually happened was that the Gangotri

glacier melted due to increasing heat at the end of Ice Age, sometime around 10,000

years BP and flowed down, initially as a lean stream. It flowed in the path dug

by the Sagaras, according to Ramayana description. That path entered what is

now Bay of Bengal. The Sagaras had dug along the east coast of India. The

Ganges had entered that path and ended at Setu. As time went by Gangotri

started melting more and more and the river Ganges started getting more water.

But by then the water level at the Bay also had risen up and the shore lines

had advanced towards land, sinking the channel of Sagaras underneath it. The

location of this channel exists close to the shoreline as the land mass of

India was slightly extended towards the Bay.

One can see the shoreline extended throughout the

east and south of India.

The Bathometry analysis of the Bay of Bengal done by

the

researchers of NIO shows 4 strands parallel to the east coast at depths of 130,

80, 60 and 30 metres in this section. They consider it to be the marks of “sea

level regressional phases” during the period between late Pleistocene and

Holocene. It must be remembered that at

the start of Holocene

(13,500 years ago), the ocean level was 120 metres lower than now. The Bay of

Bengal being higher than the Indian Ocean must have had much lower water level.

That means shore line existed until the outer most strand that was at a depth

of 130 meters. The width of this extended shore line is not given by the

researchers. But this area is enough for someone to make a tunnel. That is,

this region offers scope to believe that the Sagaras dug along this patch of

land along the shores.

This patch of land now under water is our focus of attention.

It is here the river carrying the waters of Ganga and Brahmaputra are flowing along

with the waters of Mahanadhi, Godavari and Krishna after picking up their water

enroute. This water can be noticed from to the surface up to 40 meter depth in

this length. And it flows to a width of 100 km. This is perfectly fine. But the

question is why they should take a coastal route. Why didn’t the waters of

these huge rivers just spread out in front of the estuaries?

In fact the bathymetry analysis of the Bay by NIO (here)

says that the sedimentation brought by Ganga and Brahmaputra is so thick that

it is 21 km thick at the apex of the Bengal Fan (near the estuary) and goes up

to 7 degree South where it is a few hundreds of metres think. This has made the

bottom of the Bay look plain and featureless. This also shows that the river

water had spread straight into the Bay.

The above picture shows bathymetry of Indian Ocean

along with the Bay of Bengal. One can see a light blue feature in the whole of

Bay showing a more or less plain bottom. The arrow mark shows the Ninety East

Ridge which is buried under the sediment as it nears the Indian land mass in

the north.

It is logical to expect the waters of the rivers to

spread in front their mouths. But why should they take a coastal route if not

for the presence of a coastal channel that is at a higher level than the rest

of the Bay?

(For the full map click http://mapsnmaps.blogspot.in/2014/02/bay-of-bengal.html

)

The above picture shows the coastal band and the

estuaries. Though water from the rivers had flushed into the Bay they had also

taken coastal route throughout.

The coastal strands noted in the NIO study at depths

of 40, 60, 80 and 130 meters may have a reason other than regressional coast

line. Note the route of the coastal strands mapped by the NIO and compare with

the recent discovery of the route of this river.

Route of the river mapped by NIO.

The route is the same as seen in the previous map.

What remains after the discovery of the coastal flow

of the river water is the confirmation of a verse by Valmiki in Ramayana that Sagar, the

lord of the sea (in the Bay of Bengal) as it appeared to Rama (at Rameswaram) flowed

down with the Ganga’s waters as the chief among the other river waters until

that spot. “Ganga sindhu pradhanaabhir aapagaabhi” (Valmiki

Ramayana, 6-22-22).

These waters were stopped by the Setu built by Rama’s

Varana sena. Rama praises the Setu as “Paramam Pavithram, Maha Paathaka nashanam”

(Valmiki Ramayana 6-123-21). It is because

water from the sacred rivers of Ganga, Brahmaputra, Mahanadhi, Godavari and Krishna

are available together at Setu, enabling people take a dip at all the waters at

one place.

History of Rama shows that this combo river flowed down the channel dug

by Sagara. Today’s researchers have found out that there is indeed a combo

river flowing along this route. Future research is needed to show that this

channel was facilitated by man-made action!

Related articles:

*********************

From

Fishermen point scientists to

‘river in sea’

K. S. Jayaraman

Fishermen plying on the eastern coast of India have

helped scientists discover a fresh water ‘river' that forms in the Bay of

Bengal just after monsoon season1.

Arrows showing origin of the 'river in sea' n the

Bay of Bengal all the way to the end. Locations from where fishermen collected

water samples are named along the coast.© Gopalakrishna, V. V. et al.

The ‘river in the sea’ forms in northern Bay of

Bengal at the end of the monsoon and ‘vanishes’ gradually after a while. About

100 kilometres wide, it flows southward hugging the eastern coast of India and

reaching the southern tip after two and a half months. The seasonal river

in the sea was discovered by salinity measurements of sea water samples collected

by fishermen along the coast.

The Bay of Bengal receives intense rainfall during

the monsoon. This, and the run-offs from the rivers -- Ganges, Brahmaputra,

Mahanadi, Godavari and Krishna -- bring around 1100 cubic kilometres of

freshwater into the bay between July and September.

"This very intense freshwater flux into a

relatively small and semi enclosed basin results in dilution of the salt in

seawater," says one of the lead researchers V. V. Gopalakrishna, a

scientist at the National Institute of Oceanography (NIO), Goa. The diluting

effect gets concentrated in the upper 40 metres of the bay waters, resulting in

a stark contrast between surface freshwater and saltier water below, he

says.

The presence of low salinity water (called

stratification in oceanography parlance) over the Bay of Bengal prevents

vertical mixing of sea water. This results in the accumulation of more heat in

the near-surface layers, Gopalakrishna says. The sea surface temperature

remains above 28.5°C, a necessary condition to maintain deep atmospheric

convection and rainfall. Similarly, strong salinity stratification close to the

coast would mean more intense tropical cyclones, he says.

Earlier studies have shown that salinity plays a

crucial role in influencing climate variability and cyclone activity. However,

lack of in-situ observations in the bay hampered clarity on the temporal and

spatial distribution of salinity near the coast.

To fill this gap, the NIO engaged fishermen at eight

specific stations along the east coast to collect seawater samples every five

days in clean bottles. The bottles, marked with the date of collection, have

been routinely brought back to NIO since 2005 for salinity measurements.

The new dataset revealed a salinity drop of more

than 10 grams per kilogram of water in the northern Bay of Bengal at the end of

the summer monsoon. This relatively fresh water propagates southward as a

narrow (100 km wide) strip along the eastern coast of India, according to the

scientists.

"Local fishermen have been a great help in

developing this coastal network," Matthieu Lengaigne of the collaborating

institute, French Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, told Nature

India."

This knowledge may help us validate models used to

predict cyclones evolution in the Bay of Bengal," Lengaigne says. The

study demonstrates the possibility of building a scientifically usable

observational network at low cost by relying on local communities, he

says.

Following the success of the Indian programme, Sri

Lankan oceanographers have initiated a similar network around Trincomalee and

Colombo.

While the scientists have so far focused on salinity

measurements, they contend that the coastal seawater sampling programme could

also be used for regular monitoring of other oceanic parameters such as

phytoplankton or bacteria.

References

1. Chaitanya, A. V. S. et al. Salinity

measurements collected by fishermen reveal a ‘river in the sea’ flowing along the

east coast of India. Bull. Am. Meteorol Soc. (2014) doi: 10.1175/BAMS-D-12-00243.1

*********

From

Fishermen discover river in

Bay of Bengal

By

Continuous monitoring of salinity levels for nearly

a decade confirmed the river’s presence. Photo: Special Arrangement

Movement of freshwater mass begins at

the end of the summer monsoon

Fishermen have helped oceanographers discover a

river in the sea that has been meandering its way along the eastern coast of

the Bay of Bengal (BoB) after summer monsoon. A decade-long coastal salinity

observations, carried out at eight collection points with local fishers from Paradeep downwards up to

Colachel, allowed a detailed description of this uncommon oceanic

feature.

The movement of the freshwater mass begins

at the end of the summer monsoon and survives for nearly two-and-a half months.

It also travels over 1000 km from the northern BoB to the southern most tip of

India,

say scientists.

A research paper on the formation of the “river in

the sea flowing along the eastern coast of India” was recently published in

the Bulletin of American Meteorological Society.

The presence of the river was confirmed through

continuous monitoring of salinity levels for nearly a decade, said V. V. Gopala

Krishna, Chief Scientist of the National Institute of Oceanography, Goa, the

Principal Investigator of the project supported by the Ministry of Earth

Sciences.

Sorbonne University and LOCEAN Laboratory, Paris,

and the Indo-French Cell for Water Sciences, Goa, partnered in the research

work.

The southwest monsoon roughly lasts from June to

September. During this period, water vapour collected at the ocean surface by

the powerful southwesterly winds is flushed over Indian continent and the BoB.

A large fraction of the monsoon shower reaches the

ocean in the form of runoff and contributes to the freshwater flux into the BoB

in equal proportion with rainfall over the ocean.

The large rivers — Ganges,

Brahmaputra and the Irrawaddy, and three small others — Mahanadi, Godavari, and

Krishna — together contribute approximately 1100 km of continental freshwater

into the BoB between July and September.

This very intense freshwater flux into a relatively

small and semi-enclosed basin results in an intense dilution of the salt

contained in seawater, explained the paper.

The over 100 km-wide freshwater mass that is formed

from river discharges and runoffs is transported down south by the East Indian

Coastal Current, the western boundary current of the BoB. The freshwater signal

generally becomes smaller and occurs later while progressing toward the

southern tip of India, the paper said.

The salinity distribution in the BoB may impact

cyclones and regional climate in the BoB. However, the paucity of salinity data

prevented a thorough description of the coastal salinity evolution.

This lacuna was addressed by including fishermen in sea

water sample collection process. Fishers collected seawater samples once in

five days in knee-deep water at eight different coastal stations along the

coastline. The samples were analysed at the modern lab of the institute and

compared with open-ocean samples to obtain a picture of the salinity evolution,

researchers said.

According to the research paper, the occurrence of

this river in the sea along the eastern coast of India was probably not a

generic feature that could be observed in many locations in the world.

The peculiar geography of the northern Indian Ocean

that resulted in both a massive inflow of freshwater into the semi-enclosed

northern BoB and the strong coastally trapped currents along the eastern coast

of India were responsible for the formation of the river, the paper suggested.