The

Gods of ancient Mesopotamia are many totalling to more than 3000. Yet there are

some without names whose identity is beyond the perception of the researchers

of the West and Near East but which are easily identifiable by anyone from

India. Figures resembling the divine couples of

Tirumala – Tirupati and the four faced Brahma- Saraswati,

Shiva linga, Bhuvaneswari and Hanuman are

found among the Gods of

Isin-Larsa and Old Babylonian period of the early 2nd Millennium

BCE. Housed in the Oriental Institute Museum of

the University of Chicago these figures stand out in marked contrast to

the numerous other Gods of the Mesopotamian pantheon that reached the maximum

head-count in that period. That period also witnessed the highest level of

scribal activity, creation of myths, poems and art works. Perhaps the dynasties

of Isin and Larsa and the longest ever reign of a Sumerian king falling in that

period (of Rim-Sin) attracted traders from all directions whose co-existence

led to the transmission and transfusion of their respective cultures and

god-heads. It is in this background we are going to discuss the plaques and

seals that resemble popular Hindu Gods.

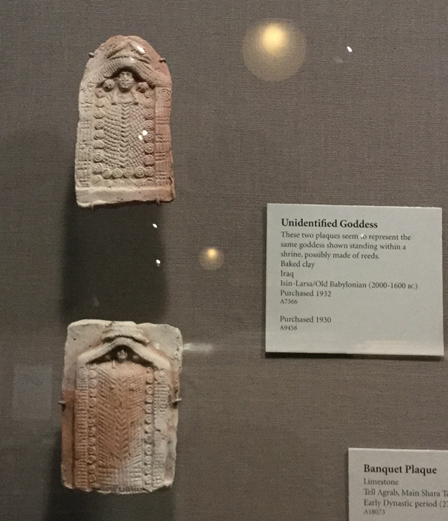

The

first figures that struck this writer on her recent visit to this Museum in

Chicago were two exhibits that bear close resemblance to Lord Venkateśvara of Tirumala

Hills! Made of some form of clay, they are mold-impressions of hardly

three inches long. Having no parallel with any other image discovered in the

region, these impressions have been termed as Goddesses, standing inside a

shrine made of reeds. But to a person coming from India, these images resemble

the God of Tirumala.

(Figure

1)

Source:

Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago.

Though

not of the same mold, the figures are hardly any different from each other. The

structure is self –revealing as male and not female. The unique style of the

decoration of the deity of Venkateśvara can be seen replicated in these

plaques. On closer examination one can find the Sankha

and Cakra (conch

and discus) resting on the shoulders like how it is for Lord Venkateśvara. The

hands are not seen but hidden inside the long decorative fabric in the front. Perhaps

this is how the decoration was done for Lord Venkateśvara in those days. But

one cannot miss out the long garlands on the shoulders and hanging down from

the head evenly on the two sides. This decoration is unique

to Lord Venkateśvara on all days since the times our elders can

recollect, but these plaques seem to convey that it has been so in the past

too.

More

importantly, the kind of flowery garlands found in these plaques are completely

absent in every other image of God or Goddesses of Mesopotamia in display in

the Museum. One figure is seen carrying flowers along with a bud (Figure 2) but

flowers and garlands were never part of accessories or decoration for the deities

or royal people of ancient Mesopotamia.

Figure 2

While

on the process of collating the facts and information on Lord Venkateśvara of

such an antiquity as that of the early 2nd Millennium BCE this

writer kept thinking that unless the consort of Venkateśvara is found in the

same region, the case for this plaque as the Hindu God Venkateśvara cannot be

effectively made out, as traditionally Venkateśvara is worshiped along with his

consort as a couple though his shrine is geographically away from that of his

consort. Surprisingly and fortunately this writer happened to stumble upon an

image in the data-base of AKG images that is exactly a look-alike of Goddess Padmavati, the

consort of Lord Venkateśvara. The data-base says that this plaque was

discovered in Old Babylon of the same period of early 2nd millennium

BCE.

Figure

3

Picture

source: https://in.pinterest.com/pin/483151866256746177/

Belonging

to the same age and same site as the Venkateśvara look-alike plaques, the above

plaque offers the best match for those plaques in terms of the mold-creation

and the decoration. This is a female and one can see the huge ear studs dangling

on the sides. Wearing ear studs is unique to Vedic culture as it follows the

ear-boring ceremony, a Vedic samskāra. Although quite a few images of

the same Mesopotamian period are seen with ear studs, they differ in style from

what is seen in this plaque. The Padmavati look-alike

is wearing a kind which is commonly found to adorn Hindu deities.

Like

Venkateśvara images, this image also has a long garland hanging from the

shoulders and another from the crown. There is a short garland from around the

neck. All these are how the Hindu deities are decorated. Rows of jewellery are

covering the upper part while the lower part looks like a fabric. This is

exactly how Goddess Padmavati is decorated even today.

The

note given along with this image says that it is a goddess

lying on the bed but it cannot be so. A cross-check with a couple of

beds (artefacts) excavated at the same site (Iraq) of Isin-Larsa

(Old-Babylonian period) and housed at the Chicago Museum shows that they are

beds with four legs. In contrast this artefact is a flat plaque with the image

of the deity cast by a mould.

Figure 4

The posture of the deity with garlands and jewellery flowing vertically down clearly indicate that the deity is not lying on the bed. Goddess Padmavati is in seated position and this plaque also shows deity in such a position with the fabric covering the portion of the seat she is mounted on. For comparison, the divine couple as they are seen today (figure 5) is given together along with the excavated plaques (figures 6 & 7).

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Further

examination of the Venkateśvara look-alike shows that the long fabric covering the

front is a woven material of some vegetation (reeds).

The crown-like head gear also looks like made of cloth. The same observation also holds good

for Padmavati look-alike, in addition to the cloth material adorning the lower

part which is actually the visible part of the entire garment that is covering

her front. The preliminary inference from this is that the decorative material for the

Venkateśvara look-alikes of these plaques came from weavers and wild vegetation

of the forest.

Of

importance to mention here is that the Tamil Sangam poems on Venkatam hills (that house Lord

Venkateśvara’s shrine) invariably speak about abundance of bamboo and Vengai trees (Ptrocarpus Marsupium) in the

region. There is reference in a Sangam composition[i] about making dresses from Vengai leaves. The fabric worn by Venkateśvara look- alikes seem to be

woven with bamboo reeds. The big, round flowers of the garland look like the products

of Vengai trees (figure 8).

Figure 8

Only 1000 years ago, flower gardens

growing specific flowers for the Lord were created at the instance of Sri

Ramanujacharya. This conveys that

until then the deity was decorated with wild flowers and products of the forest.

The plaques unmistakably reveal the olden ways of using forest products for decoration.

The continuing practice of

using a long cloth as a garland (Thomala) and

around the head as a crown for Lord Venkateśvara seems to be the legacy

of the olden practice that we can make out from the plaques.

Weavers’ deity.

The

woven material dominating the decoration of the images of the plaques

pre-supposes the existence of weaver communities that were preparing the

fabrics for the deity. As regular suppliers of the vegetative fabric and cloths

to the deity, those communities could have developed close allegiance with the

deity to the extent of treating it as family deity and a personal identity

wherever they went. The Venkateśvara look-alike

appearing in Mesopotamia 4000 years ago could not have happened without such

communities moving over to Mesopotamia obviously for trading purpose.

Even

today specific weaving communities are preparing the cloths for Lord

Venkateśvara. Though their service started a few centuries ago, the presence of

this practice can only be a continuation of an older tradition. The huge size

of the deity required specially woven cloths for this deity and not just any

cloths. This emphasises the fact that specific weaving

communities must have been engaged in preparing the fabric in the remote past

too.

A

couple of bronze objects looking like weaver’s

implements unearthed in Isin-Larsa in the early part of the 2nd Millennium

BCE and bearing resemblance to Indian images strengthens the notion of the presence of weavers of Indian origin in that region.

Figure 9 shows one of those objects whose purpose is not known but could fit

with the weaver’s kit.

Figure 9

Source:

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1998.31/

The

female figure in the middle looks more Indian

than any Mesopotamian female figure found so far, in the same period or any

time before or after. The jewellery in ears, neck,

waist and hands are typical Indian style that we find in old temple sculptures

of south India. The men also look different from the male figures of the

comparative period. Their adornments, facial looks and cloths are Indian in

style.

Figure

10 shows yet another bronze image found in the same place, same era. The roller

in the image looks like a bobbin used for winding thread.

Figure 10

Source:

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1980.407.1/

The

male figures in this piece are also different from contemporary Mesopotamian

males in other art works. A shaven head with a forelock

is unknown in Mesopotamia, though completely shaven heads are found in

Akkadian period that preceded the period under discussion. The forelocks in these images are

characteristic of Cholia people of Tamil lands and also were witnessed

across India in the past. A figurine found in Harappa

has a similar forelock (figure 11).

Figure 11

Cossacks of Ukraine also sported similar

forelocks but their early presence in Mesopotamia has no back-up support. The Indian-ness of these objects

and the plaques of Venkateśvara look-alikes weigh in favour of a weaving

community to be present in south Mesopotamia in early 2nd Millennium

BCE.

Further

back in time, weaver’s presence is also noticed in Uruk

period of 4th Millennium BCE. The location is close to

Isin-Larsa. Figures 12 and 13 show three cylinder seal impressions of women

engaged in weaving, kept in Chicago Museum.

Figure 12

The pig tailed women bear close resemblance to the seven women of

Mohenjo-Daro seal that appeared 600 years later

(Figure 14)

For

closer comparison, the Uruk and Mohenjo-Daro seals are shown side by side in

figure 15.

Figure 15.

The

pig tailed women with similar costumes appearing in Uruk seals engaged in what

looks like looms (textile making) give rise to

an opinion that the Mohenjo-Daro

seal was a ceremony done by weavers! This similarity is brought out here

to justify the presence of

weavers in south Mesopotamia in late 4th to early 2nd

Millennium BCE who shared similar physical traits with people of Indus

civilisation (India).

Available

research works done so far have established that Lothal

has served as a transit point from India to Mesopotamia via Persian Gulf.

The easiest route is through Persian Gulf and not

through North West India. Dr B.S During in his thesis on “Seals in

Dilmun society”[ii]

established on the examining the seals how Dilmun (Bahrain) served as a nodal point of trade for

those entering the gulf that further takes them to south Mesopotamia. The trade routes from Lothal to Dilmun and Mesopotamia in the

period 2800-1500 BCE is reproduced in figure 16 from his paper.

Figure 16

Authors

Steffen Laursen and Piotr Steinkeller

established that military conquests of Sargonic kings of Babylonia

were aimed at controlling trading points and ensuring smooth business for their

own subjects[iii]

. Trade and commerce were the buzz words of rulers of that time.

It

is worth noting here a parallel

incident from Mahabharata. It is everyone’s knowledge that almost every

ruler of India participated in the war. This could be possible only if the

participating countries had some stakes in winning the war. The Pandyan king by

name Sarangadwaja refused to side with the Pandavas as he wanted to avenge Krishna for

having killed his father (previous enmity). But he was discouraged from

doing that by his friends in the Pandava camp (Drishtadymna)[iv]. What could have weighed in favour of keeping aside his

personal enmity and siding with the Pandavas? Only if a larger good is

assured in return for his country, this Pandyan king could be expected to have

for kept aside his personal grouse. That larger good could in all possibility

be economic and commercial

returns.

If

by siding with the Pandavas and Krishna, the Pandyan traders could get easy and

hassle-free access to the ports of Dwaraka (Gujarat) in the event of Pandavas

winning the war, then the Pandyan king had no other choice than burying his

personal enmity and backing up the Pandavas. The

traditional date of Mahabharata war coinciding with Early Harappan period and the

rise of Lothal as a busy port concur well with Indic history as revealed in

Mahabharata. By keeping control over the

ports in west coast of Gujarat, entire South India that sided with Pandavas

stood to benefit while the north Indian traders

could have chosen Gandhara- route that was with Kauravas before the war.

Until

now everyone has been talking about Indus regions. There is absolutely no thought about south India. The Tamil

kingdoms existing for long and grand rivers draining the lands of south India

offer enormous scope for evolution of economically

profitable occupations well before the Indus civilization. The nearest points of transit to enter west Asia and

Europe were the ports of Arabian Sea. The closest and safest port (from

monsoon vagaries) was Lothal.

It is in this backdrop, the movement of

weavers of south India who were once serving Lord Venkateśvara, to Mesopotamia

through western ports and Persian Gulf looks very much viable. Both Gujarat (Saurashtra) and Andhra Pradesh are known for

traditional weaving practices. Anyone from these regions could have

taken their families and family deities to Middle East.

Conducive

atmosphere for trade in Isin-Larsa period had attracted people from all sides.

The culture, language and religious beliefs of all the new entrants were

absorbed leading to the formation of Anunnaki – group of various

and numerous deities that dominated Mesopotamia for over two millennia later. The Hindu deities too have contributed to the diffusion of

Thought (to be discussed in upcoming articles) but Venkateśvara stands

out from other deities in this regard. There is no trace of Venkateśvara in Anunnaki and no trace of the

people (who carried memory of this deity) further in time. May be they

were absorbed in the local community or had gone beyond the Middle East. This

probability must be borne in mind in any genetic study that finds a link with south Indians or

Indians.

This

monograph cannot end here without ascertaining an antiquated presence of Lord

Venkateśvara at Tirupati hills on par with the date of the plaques found in

Isin-Larsa 3500 years ago.

Antiquity of Venkateśvara temple at Tirupati.

There

are literary evidences from Tamil Sangam texts in support of antiquity of Lord Venkateśvara.

The

earliest reference to the presence of this deity on top of the hill is found in

the 2000 year old* Tamil Epic called Silappadhikaram.

Tirupati was known as ‘Venkatam’ in those days.

A Brahmin from Māngādu near Kudamalai (Kodagu) on a pilgrimage to worship

Vishnu at Srirangam and Venkatam describes the deities of these two places. As

per his description the deity at Venkatam was standing in between the sun and

the moon, with the conch and discus in his hands and adorned with beautiful

garland on his chest and a fabric dotted with golden

flowers.[v]

The reference to sun and the moon is because of the strategic location facing

the east as one can see the luminaries on the two sides of the temple and crossing

the temple every day.

This

description conveys that this deity was popular 2000

years ago. Yet another reference to Venkatam comes in the same text when

a newly married couple belonging to Northern Chedi

travelled to Pumpukar to witness the Indra festival.

After celebrating the Festival of Kāma deva (on the

Full Moon day of Phalguna month when the Sun is in Pisces – today’s Holi

festival), they crossed the highs of Himalayas and then the river Ganga

and reached Ujjain. From there they went to Venkatam hills before going to

Pumpukār. [vi]

Figure 17

This

description at once changes the currently held popular views on Holi festival

and the location of Northern Chedi. In the tourist map for someone coming from

the Himalayan region, Venkatam hills being held as an important place of

destination is something that conveys more than just a hill station or a

stop-over. The popularity of

Lord Venkateśvara even as early as 2000 years ago is the inevitable

message of this travel map.

Further

back in time, Venkatam gets frequent mention in Tamil Sangam texts. The grammar

book of the 3rd Sangam, namely Tol

Kāppiyam begins with the name Venkatam as

the northern boundary of the speakers of Tamil language.[vii] Tol

Kāppiyam was composed at the beginning of 3rd Sangam after the

previous Sangam location was lost to the seas. By the calculation of the Sangam

age-years given in another text called “Iṟaiyanār

Agapporuḷ Urai”, the previous location was lost in 1500 BCE which

means the reference to Venkatam

as northern boundary had been made soon after 1500 BCE.

The

existence of the name Venkatam as early as 1500 BCE reiterates the presence of

the God Venkateśvara even at that time as the etymology of ‘Venkatam’ is traced

to ‘burning the body (of sins)’. It is VenGhata

where ‘ghata’ means pot, a reference to human body. The hymns of

Vaishnavite saints (Alvars) also convey that this God removes the sins of

previous and current births. In other words the Lord

burns the sins of the human body. So this goes without saying that the hill got the name from the

deity and not vice versa. The reference to Venkatam in Tol Kāppiyam

is proof of existence of this deity from before 1500

BCE.

How widespread was the popularity of Venkateśvara in

olden times?

The

reference to Venkatam hills as the northern boundary of Tamil speakers opens up

considerable part of South India to have been inhabited by those who spoke

Tamil. This is because Venkatam is a range of mountains

running from north to south in the form of a cobra. Abodes of Gods dot the important organs of

the cobra. Puranic description of Venkatam is such that Nallamala housing Srisailam forms the tail of the cobra. Ahobilam is located at the trunk. Tirupati is at the back of the cobra’s hood while the mouth

can be identified by Kalahasti. A Sangam poem also reiterates the idea

that the range is a house of Gods.[viii]

Figure 18

The regions on both sides of the Venkatam range had people finding mention in the Tamil Sangam compositions. While Nannan was associated with Konkan, Velir were reigning from Kudremukh in Karnataka. On the eastern side, Kallada was the native place of Sangam poet ‘Kalladanar’. In all his compositions, he describes the scenes of Venkatam hills, the ruling dynasty of Pulli of Venkatam and the difficulties in crossing this range. While all his compositions found in Aganānuru describe the difficulties faced by those going for trade while crossing the range from south to north, in one composition in Purananuru[ix] he describes a scene of drought induced poverty that drove the hero into crossing Venkatam from north to South to reach Tamil kings.

Figure 19

From

the Sangam poetry it is known that the Venkatam range

was a well-known landmark for people going for trade and livelihood. In

all those trips the main deity of the hills, Venkateśvara must have been worshiped to ensure safe

journey and return. With the range spanning across South India, the

deity also must have been a popular one throughout South India. From the

Silappadhikaram narration of the newlywed couple of Northern Chedi making a

stop at Venkatam it is known that Venkateśvara was popular throughout India 2000 years ago.

Who

among them had gone to south Mesopotamia taking with them Venkateśvara and his

consort Padmavati? There is a clue to

this which we will discuss in the next part of this article.

(to

be continued...)

*

Silappadhikaram can be dated at 2000 years BP based on a cross reference from a

Satakarni who helped the Chera King Senguttuvan in his northern

expedition. Silappadhikaram makes a reference to a victory over the Yavanas by

this king during the expedition (Ch 28: lines 141-142). Gautamiputra

Satakarni was the only Satakarni who scored a victory over the

Yavanas. This conveys that together they have fought and won the Yavanas. From

the date of Gautamiputra Satakarni, the Silappadhikaram date can be made

out as belonging to the beginning of the Common Era.

[i] Kurinji Paattu

[ii] During, B.S., 2011, “Seals

in Dilmun Soceity”, University of Leiden.

[iii] “Babylonia, the Gulf Region and the Indus: Archaeological and Textual Evidence for Contact in the Third and Early Second Millennia BC (Mesopotamian Civilizations)” https://www.harappa.com/content/babylonia-gulf-region-and-indus-archaeological-and-textual-evidence-contact-third-and-early

[iv] Mahabharata: 7-23

[v] Silappadhikaram: Chapter 11: lines 41-52

[vi] Silappadhikaram:

Chapter 6: lines 1-33

[vii] Tol Kāppiyam: Line 1

[viii] Agananuru: 359