Previous part: Karikal Chola who built Kallanai (Grand Anicut) was a contemporary of Adi Shankara

Karikāla’s history before Iḷam Thirayan

In the history of Chola-s we find more than one king

ruling the Chola country. The chief king was ruling from the main capital,

which was Pūmpukār in the pre common era. Uraiyūr was also a capital but occupied

by the son or a sibling of the chief king. For example, Nalam Kiḷḷi, also known

as Set Senni (சேட் சென்னி) was praised as ‘Uṛanthaiyon’ உறந்தையோன்) – the one who belonged to Uraiyūr

in the 63rd verse of Purananuru. But he was praised for

having a naval fleet in the 382nd verse of Purananuru which would

have been possible if he was in control of Pūmpukār.

His son was ‘Kuḷamuṛṛatthu thunjiya Kiḷḷi

Vaḷavan’ (குளமுற்றத்துத்

துஞ்சிய கிள்ளி வளவன்). He

also belonged to Uraiyūr as per the 39th verse of Purananuru.

He had more verses in praise of him than even Karikāl Chola. Both he and his

father Nalam Kiḷḷi were praised by Kovūr kizhār

(கோவூர் கிழார்), giving the impression that both the father and the

son were ruling simultaneously with their base in Pūmpukār and Uraiyūr

respectively.

At the same time, two brothers of Nalam Kiḷḷi were

also given rulership of some part of the Chola country because there are verses

in praise of them too. One of them was ‘Māvaḷatthān’ (மாவளத்தான்) praised in the 43rd verse of Purananuru. Another brother

was Uruva pahrēr Iḷamsēt Senni, the father of Karikāl Chola.

Uruva pahrēr Iḷamsēt Senni died when Karikāl chola was

still in his mother’s womb. The history of young Karikāl chola picked up from

the Sangam age texts show that the Chola country went into the hands of enemies

for a brief time. Karikāl Chola had grown in the custody of his maternal uncle,

Irumbidar Thalaiyār (இரும்பிடர் தலையார்). His enemies found him out and imprisoned him. An

attempt was made to kill him in the prison by setting fire to the prison but

Karikāla managed escape. However, his leg suffered burn injuries, due to which

he came to be known as Karikāla – the one with burned leg. However, Tiruvālangādu

copper plates give a different justification for his name as Kali-kāla – the

one who was Yama to Kali.

Soon Karikāla gained the country and scored a major

victory in a place called ‘Veṇṇi Paṛanthalai’ (வெண்ணிப் பறந்தலை) in which he defeated the Pandya king, the Chera king

and eleven minor chieftains. In yet another war in a place called ‘Vāgai Paṛanthalai’ (வாகைப் பறந்தலை) he defeated nine kings.

With all these, his name appears associated with a

place called ‘Idaiyāṛu’ (இடையாறு) and not Pūmpukār! ‘இடையாற்றன்ன நல்லிசை வெறுக்கை’ says 141st verse of Agananuru.

At the same time, ‘Kuḷamuṛṛatthu thunjiya Kiḷḷi Vaḷavan’ the son of his elder paternal uncle,

Nalam Kiḷḷi also was ruling from Pūmpukār. This is made out from the fact that both

(Karikāla and Kiḷḷi Vaḷavan) were praised by the

poet Nakkīrar. Sometime later Karikāla became the Chief king in Pūmpukār. This

could be possible if the direct heir of Kiḷḷi Vaḷavan no longer existed or Karikāla

was a preferred Chief than the son(s) of Kiḷḷi Vaḷavan.

Around this time, another Chola King also existed

whose son was Iḷam Thirayan.

Iḷam Thirayan’s life history

The story of Iḷam Thirayan is found in two chapters of

the text, ‘Manimekalai’. He was the hero of the Sangam poem, ‘Perum Pānāṛṛu

Padai’ (பெரும் பாணாற்றுப் படை)

which identifies him located

in Kanchi. He caused a text in his name – ‘Iḷam

Thirayam’ (இளம் திரையம்)

to be inaugurated in the

Sangam Assembly. This is told by Nakkīrar in his commentary to ‘Irayanār Agapporuḷ’

as an example for naming a book after the one who caused the poet to write it. One

will be surprised to know about another book mentioned in these lines. It was ‘Sātavāhanam’ that was caused by a Sātavāhana king

to be composed in Tamil and inaugurated in the Sangam Assembly. Both these

books have not survived.

The birth of Iḷam Thirayan is told in the 25th

and 29th chapters of Manimekalai. There was Chola king by

name, ‘Nedumudi Kiḷḷi’ (நெடுமுடிக் கிள்ளி) ruling from Pūmpukār. Pīlivaḷai (பீலிவளை)

was the daughter of Vaḷaivaṇan, (வளைவணன்) the

Nāga king. The Chola king met Pīlivaḷai and fell in love with her. They spent

time together for a few weeks after which she left. She was pregnant when she

left and gave birth to a male child. Wishing to get back to her parents, she

decided to send the child to its father, the Chola king. She met a merchant

(Kambaḷa Chetti – கம்பளச் செட்டி)

who was on his way back to

Pūmpukār in a ship. She entrusted the child to him, gave the details about the

child’s identity as the son of the Chola king and asked him to hand over the

child to the king.

Unfortunately, a sea storm struck the ship. The ship

sank and the child was lost. The merchant who happened to be a distant ancestor

of Kovalan (the husband of Kannagi) managed to swim towards Pūmpukār and

delivered the news about the child to the king. The shocked King immediately

went about searching for the child. As a result, he ignored his kingly duties.

In his anxiety to find out the whereabouts of the child, he did not conduct the

Indra festival. This invited a curse from the deity that Pūmpukār would

suffer inundation.

Only this much of the story is found in Manimekalai.

However, there is an oral tradition that the child was recovered by the Chola

king, wrapped by a creeper called Ātoṇdai (ஆதொண்டை). The child was recovered on the shores of Kanchi, and this made the king

give him the Kanchi region for him to rule. Since he was protected by the waves

of the sea, he was named Thirayan and the protection by Atoṇdai lent the

name Toṇdai Maṇḍalam to the regions of Kanchi.

What relationship Nedumudi Kiḷḷi had with Karikāla is

not known, but he must have been a paternal uncle of Karikāla when Karikāla was

positioned in Idaiyāṛu. Upon the exit of Nedumudi Kiḷḷi, Karikāla must have

taken position in Pūmpukār. It was he

who built the walls of Kanchi and invited people to reside there. At that time

Kanchi was within the dominion of Trilochana Pallava – an early Pallava

who had his base in Dharaṇikota (today’s Amaravathy) according to

several sources. Subsequently Adi Shankara arrived at Kanchi and Karikāla served him. This

seemed to have happened sometime after Iḷam Thirayan was

made the chief of Kanchi because the locations given in Perum Pānāṛṛu Padai

reveal that the division of Kanchi had not yet taken place when that text was

composed.

Kanchi in Iḷam Thirayan’s

period

The text Perum Pānāṛṛu Padai composed in praise of Iḷam Thirayan narrates the route taken by the poet to

reach the palace of Iḷam Thirayan. Some of them are identifiable as they

continue to exist today. After passing through habitats of various kinds of

people the poet reached the seashore where he saw a Lighthouse. In six lines,

the Lighthouse is described as a building on top (of something not mentioned) which

was difficult to access. A ladder was kept leaning on it. Only trained people could

climb to the top. A huge lamp was burning all through the night to guide the

ships.

After reaching the Lighthouse, the groves on the seashore

were mentioned. Upon crossing the groves, the poet reached a Highway that

passed through many small habitats and villages and a Vishnu temple in a place

called ‘Tiruvehka’ (திருவெஃகா). The route from the Lighthouse and Tiruvehka is a

crucial hint on the topography because even today there is a Highway passing

through Tiruvehka from the Lighthouse.

Today two Lighthouses exist – an old one and a new

one. The old Lighthouse exists on a huge rock and is regarded as the oldest in

India. There is a temple on top of it. The Light was burning on top of the

temple.

Old Lighthouse

The structure of the old Lighthouse as it exists today

was re-modelled by the Pallava-s in 640 CE, but we are talking about the

Lighthouse of the pre-Common Era. In the Pallava-made structure, the top

portion was built on the Mandapa of a Durga temple. Presently it is known as Olakkanneshvara

temple. In the Sangam age a ladder was used to reach the top, but the Pallava-s

replaced it by cutting steps on the rock to reach the top.

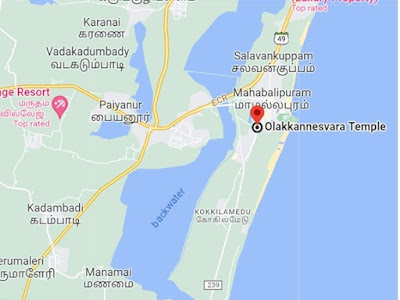

Location of the Old Lighthouse (Olakkanneshvara temple)

Today this old Lighthouse is UNESCO heritage site. An

article by UNESCO states that this structure is one of the oldest models that inspired

the Pallava-s to construct Shore temples (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/249/ ). A new Lighthouse is built close to it.

New Lighthouse

After crossing the backwaters, the Highway starts. It

goes to Tiruvehka (also known as ‘Sonna vannam seitha Perumal’ temple சொன்ன வண்ணம் செய்த பெருமாள்) but only after crossing Varadaraja Swamy temple! While

passing through this route, no one can miss the Varadaraja temple which is on

the way. After crossing the Varadaraja temple, Tiruvehka can be reached in one

and a half kilometers.

Route from the Lighthouse to Tiruvehka exists today as described in Sangam text.

The Sangam text refers to Tiruvehka but not Varadaraja

temple. This makes a strange reading because today Varadaraja temple is more

popular than Tiruvehka temple by size and the number of devotees visiting it. Why

did the Sangam poet not make a mention of it? Was it because it was not popular

then and was very small and insignificant?

In this context it is worth mentioning the observation

of Mr. K.V. Raman in his book ‘Sri Varadaraja Swami temple Kanchi: A

study of its history, art and architecture’ (1975) that Varadaraja Swami was

not sung by many Alwars, more notably by those born in Kanchipuram. He says,

“It is rather strange that Alwārs like Poigai who was

born in Kanchi and Tirumalisai (Alwar) who spent considerable time in the city (and

particularly at Tiruvehka) have not referred to the temple at Attiyūr

(Varadaraja temple). Nor has it ben sung by Tirumangai Alwār who has composed

hymns on even at the smaller temples at Kanchi like Uragam, Pādagam, Tiruvehka

besides the Parameswara Viṇṇagaram.”

Varadaraja Swami is identified as one residing in Attiyūr

where Atthi refers to hasti, the elephant. As per the temple legend the

deity appeared as ‘Hasti-giri’ an elephant-like mount. In one of the

verses on Vishnu at Parameswara Viṇṇagaram, Tirumaṅgai Alwār refers to ‘kacchi

mēya kaḷiṛu’ (கச்சி மேய களிறு)– the elephant in Kanchi - which is treated by

scholars as referring to Varadaraja Swami. Apart from this reference, only Bhūthathālwār

talks about Varadaraja swami as Attiyūrān who flies on the bird (அத்தியூரான் புள்ளை ஊர்வான்).

Other than this, there are references

to only the walls of Kanchi in a couple of verses which indicate that such

verses were composed after Kanchi was re-modelled by Karikāla.

The absence of mention about the Varadaraja Swami

temple on the way to Tiruvehka in the Sangam text conveys just one meaning –

that the temple was not yet built. Sometime after the verse was composed, the

re-building of Kanchi must have happened. Iḷam Thirayan cannot be credited with re-building the city, for,

there is a specific mention about Karikāla in the Tiruvālangādu plates as one

who re-modeled the city. Only Karikāla based at Pūmpukār was the Chief and Iḷam

Thirayan was a subordinate king to him. It can be said that Karikāla had a

greater say in the affairs of Kanchi though technically it was under the

tutelage of Iḷam Thirayan, because it was Karikāla who snatched Kanchi from Trilochana

Pallava and brought it under the Chola control.

(to be continued)