El Nino is a modern term but

our land of ancient Tamils had always experienced heavy rains in the solar

months of Aippasi and Karthigai. This is made out from the adage “Aippasiyil adai mazhai, Karthigaiyil Gana mazhai”( ஐப்பசியில் அடைமழை, கார்த்திகையில் கனமழை).

The Paripaadal verse on Pavai Nonbu (verse no

11) describes a scene of flood ravaged land that comes to house smaller water

bodies called “KuLam” by the time the month of Margazhi

begins. For this reason the month of Margazhi was also known as “KuLam” (குளம்).

Our ancestors have laid a

fantastic system of hydrology to channelize the flood waters and also to store

the excess water for use in dry months. This network can be depicted as below.

(Note: Click on the pictures to see enlarged version)

The network comprises of

River water overflowing into subsequent and smaller water bodies.

River > Lakes (Yeri) >

KaNmai > KaraNai > Thaangal > Yenthal > OoraNi > KuLam >

Kuttai.

These names themselves show

that Pazhavanthaangal and Vedanthaangal were water bodies once. Even now there

are some street names as Thaangal street in

different parts of Chennai. It means there was once a water body adjacent to

that street.

The topography

and hydrology of Chennai is such that Chennai is a low lying area with

an average elevation of only 6.7 metres above

the mean sea level, with many parts of it actually at sea level. This landscape of Chennai makes it a marshy land that

drains rain water into the adjacent sea. Chennai was indeed dotted with

numerous tanks and lakes as per old maps of the British. Agricultural activity

was going on at that time supported by these tanks.

The oldest map that I could

get from a Google search was of

1893. It shows a long semi curved tank spanning in between Coovum river

and Adyar river. (Below)

At that time this tank was

identified at two places (in the map) as Nungambakkam tank and Mylapur tank. The ‘Long Tank Regatta’ was held in 1893 “on

the fine expanse of water that starts from the Cathedral Corner (once where

Gemini Studio’s property was) to Sydapet”.

The southern end of this

tank is linked to Adyar river near Saidapet. The map of 1914 gives clear details of this tank

which by then acquired the name “Long Tank”. The inset in the 1914 map (below)

shows that this link between Long tank and Adyar river is man-made. This must

have existed much before the British came. This is the proof of how our

ancients thoughtfully connected the waterways and the drainage system.

The Vyasar

padi tank in this map was also a huge one at that time. But it is

missing at present. The Vyasarpadi Tank was one of the most important tanks of

Chennai along with 9 other tanks namely Perambur, Peravallur, Madavakkam, Chetput, Spur, Nungambakkam,

Mylapore/Mambalam, Kottur and Kalikundram.

All of them have vanished

now.

The

first official encroachment of water bodies in Madras started in 1923

with the plan to reclaim land from the Long Tank. The party that was in power

at that time was none other than the root cause of the Dravidian ideology namely

the Justice Party. The

party that was unambiguously based on anti-Brahmanism and atheism and had brain

washed the masses with a non-existent Dravida ideology found no qualms in

destroying a major water source of Madras.

Reclamation of land from this tank was

started from 1930 by the

same Justice Party, to create the Mambalam

Housing Scheme on 1600 acres that gave rise to Theagaroya Nagar or T. Nagar

(named after the founder of Justice Party). Destruction of hydro system in the name of development was started by

these Dravidian ideologists.

From 1941 onwards, further reclamation

was done in Nungambakkam. At the westernmost end of the Tank, 54 acres were

reclaimed for the Loyola College campus.

In 1974 what was left of the Tank was

reclaimed to give the city the Valluvar Kottam campus alongside Tank Bund Road by none other

than Karunanidhi.

It must be noted that Valluvar

Kottam was constructed right at the deepest part of the Long Tank. Old

timers recall that for many years and year after year, Valluvar Kottam was

water logged during the rainy season. It would have been apt had they named it as Valluvar Ottam or Valluvar

Theppam (Float)!

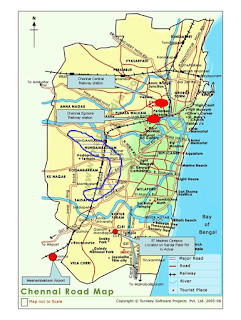

The following map is that of Chennai

today. The location of the missing Long Tank

(rough sketch) is shown in the next map.

The Long Tank formed the

western boundary of Madras of those years. The Mount road was laid to the east

of it. Today’s Mambalam, Mylapore, Panagal Park, Nungambakkam etc were built on

this Tank. No wonder when

Adyar river overflowed, the waters found their natural slopes in these areas in

the recent floods.

A map

drawn 65 years ago shows a

sprinkle of numerous water bodies such as Yeris and Kulams all over present day

Chennai. They were also well connected to drain extra water in times of flood. This

map is shown below.

The gray areas are the water

bodies which would remain dry in summer but can house rain water in the rainy

season.

Today the gray areas are all

closed down with habitations. Needless to say why most parts of Chennai is

water logged even by short spell of rains.

The presently available

water bodies –from among the network in the above map - are shown in the

picture below.

In a good monsoon year,

where will the rain water go? All the gray areas become water logged.

A compilation of

reports on areas of Chennai which were once water bodies or drainage canals.

·

Two main rivers Cooum

and Adayar cross Chennai. Chennai’s

periphery once hosted a massive wetland,

which provided a natural flood control barrier in the past.

·

Adyar,

Cooum, Kosasthaliyar and the man-made

Buckingham canal are the macro drainages. They

have a huge capacity to carry flood waters which is by now reduced to half the

capacity due to encroachments.

·

The river Coovum which was once a fresh water source is now

reduced to a massive,

stinking sewer heaped with the

waste generated by a heaving metropolis.

·

Similarly, rampant

encroachment and urbanisation in its upstream reaches has sapped

the ability of the Adyar river to carry flood water.

·

Another key waterway,

the Buckingham Canal, is also choked with silt

and sewage. So, when Chennai floods, there aren’t enough unobstructed channels

for the water to get out.

·

Around eight

medium drainage canals drain in to these rivers. These are the Otteri Nallah, Virugambakkam canal, Arumbakkam canal,

Kodungaiyur canal, Captain Cotton canal, Velachery canal, Veerangal Odai and Mambalam

canal. They are all missing now.

·

Two decades ago,

Chennai had 650

water bodies—including big lakes, ponds and storage tanks. The current number stands at around 27,

according to the NIDM study. Even those water bodies that have managed to

survive are much smaller than before. For instance, the total area of 19 major

lakes in the city has

nearly halved from 1,130

hectares to about 645 hectares.

·

Other water bodies such

as Ullagaram, Adambakkam, Thalakanacheri, Mogappair and

Senneerkuppam are considered beyond restoration. In the case of water

channels like inlet and outlet they have completely disappeared

·

There are about 3000 tanks and ponds big and small in the Chennai

area. Some of the important tanks are Madipakkam,

Velachery, Thoraipakkam, Pallavaram, Madambakkam,

Maraimalainagar, Kilkattalai, Pallikaranai, Adhambakkam, Puzhudhivakkam,

Thalakanancheri, Kovilambakkam, Chitlapakkam

and so on. These tanks can be classified as ENDANGERED.

·

The Adambakkam Lake is being closed due to the Metro Rail

work and a concretised road leading from Velachery to GST Road is being built.

·

Madipakkam

Lake has become a dumping yard for garbage

and the water is not fit for any use. And on the other side construction of

buildings is going on apace.

·

Puzhudhivakkam Lake was

once an important reservoir and used to host a number of rare birds. This

valuable natural resource has now been gradually converted into a housing

colony. Inundation in Puzhudhivakkam and Madipakkam is caused by the

disappearance of the Veerangal Odai which connects the Adambakkam and the

Pallikaranai marsh.

·

Chitlapakkam

Lake was once the water source for the

Sembakkam and Hastinapuram villages. The total area of this lake is 86.86 acres

which has subsequently shrunk to 47 acres due to encroachments such as the

development of the district court, bus terminal and the Tambaram taluk office.

·

Chitlapakkam lake is

getting water through 3 channels from the foothills. However, in this region

the water table level is higher than in other areas. This lake is further

contaminated by household sewage and waste from commercial establishments.

·

Chennai,

Thiruvallur, Kancheepuram and Chengalpattu are hydrologically integrated. As

per the tank memoir prepared by the British, there are 3,600 tanks in these

districts and the surplus from around 20 tanks have

also contributed to inflow in Chembarambakkam. All these have been encroached now.

·

Pallikaranai marshlands,

which drains water from a 250 square kilometre catchment, was a 50 sq km water

sprawl in the southern suburbs of Chennai. Now, it is 4.3 sq km—less than a

tenth of its original.

·

Pallikaranai marsh

acted as a natural flood sink when the rains overwhelmed Chennai. “The marsh

that was till about 30 years ago spread over an area of more than 5000 ha

(hectares) has been reduced to around one-tenth of its original extent due to

anthropogenic (manmade) pressures. The free flow of water within the entire

marsh has been totally disrupted due to mega construction activities and

consequent road laying,” a 2007

study by a group of German and

Indian scientists noted.

·

The growing finger of a

garbage dump sticks out like a cancerous tumour in the northern part of the

marshland.

·

Two major roads cut

through Pallikaranai waterbody with a few pitifully small culverts that are not

up to the job of transferring the rain water flows from such a large catchment.

The edges have been eaten into by institutes like the National Institute of

Ocean Technology (NIOT). Ironically, NIOT is an

accredited consultant to prepare environmental impact assessments on various

subjects, including on the implications of constructing on water bodies.

·

There were 16 tanks

downstream of Retteri called Vyasarpadi chain of

tanks. Kodungaiyur tank was one among them. Now,

there is no sign of them.

·

There was also a tank

in Thirumangalam area which is missing now.

·

There were once 13

water bodies in Neelankarai (the name itself

shows that this place was on the banks of a water body). Only 2 lakes remain

now.

·

The Virugambakkam drain was 6.5 km long and drained into

the Nungambakkam tank. It is now present

only for an of extent of 4.5 km. The remaining two km stretch of the drain is

missing.

·

Nungambakkam

tank (part of Long Tank) was completely filled

and built. This along with the loss of Koyambedu drain has resulted in the

periodic flooding of Koyambedu and Virugambakkam areas.

·

The surplus channels

connecting various water bodies in western suburbs such as Ambattur and Korattur have been encroached upon.

·

The water body in Mogappair has almost disappeared.

·

The Veerangal Odai that connects the Adambakkam lake with

Pallikaranai marsh ends abruptly after 550 m from its origin and the remaining

part is not to be seen. This causes inundation in places such as Puzhithivakkam and Madipakkam.

·

The Chennai Bypass connecting NH45 to NH4 blocks the east

flowing drainage causing flooding in Anna Nagar, Porur,

Vanagaram, Maduravoyal, Mugappair and Ambattur.

·

The Maduravoyal lake has shrunk from 120 acres to 25

acres. Same with Ambattur, Kodungaiyur and Adambakkam

tanks.

·

The Koyambedu drain and the

surplus channels from Korattur and Ambattur tanks

are missing.

·

The South Buckingham

Canal from Adyar creek to Kovalam creek has been squeezed from its original width

of 25 metres to 10 metres in many places due to the

Mass Rapid Transit System railway stations.

·

Important flood

retention structures such as Virugambakkam, Padi and

Villivakkam tanks are no longer there.

·

Elevated

Express freight corridor from Chennai harbour

to Maduravoyal had reclaimed a

substantial portion of the Coovum’s southern bank drastically reducing the

flood-carrying capacity of the river.

·

The lost water body of Velacheri between the year 2000 and 2015 is shown

below.

·

The two drainage canals

that went missing when I.T park was developed in Siruseri.

·

Water bodies shrunk by

the Sholinganallur I.T park is shown below.

·

A comparison of the

Chennai topography with the missing Long Tank is shown below. In the figure, No1 shows Coovum river. No 2

shows Adyar river. Where is No 3?

The

lesson

We have robbed the natural habitation of Chennai’s

water routes. They have paid us back.

***********

Sources for this

compilation:-